Interview with Dr. Nancy Ascher: The First Woman to Perform a Liver Transplant, and Still Saving Lives

Featured on Netflix's Surgeon's Cut, Dr. Nancy Ascher talks about focusing on the long-game, women at home and in the workplace, what it's like to work with her husband, and the future of liver disease.

By Victoria Oldridge

Dr. Nancy Ascher has devoted her career to organ transplants and transplant research, completing her undergraduate and medical education at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She then went on to complete a general surgery residency and clinical transplantation fellowship at the University of Minnesota.

Dr. Ascher joined the faculty of the Department of Surgery at the University of Minnesota in 1982 and was named Clinical Director of the Liver Transplant Program. She was recruited in 1988 by the UCSF Department of Surgery to build a liver transplantation program. In 1991, she was appointed Chief of Transplantation, an expanded role that included liver, kidney and pancreas transplants.

Truffld: Today's workforce is more transient than it used to be, with current generations projected to switch careers – much less companies/roles – six or more times throughout their lifetime; the long game, like dreaming of becoming an astronaut, for example, is less common, while instant gratification careers are the norm. You had the foresight to know early on that you wanted to choose a profession that would engage you for decades. How can we bring some of that approach back?

Dr. Ascher: I guess some of the millennials to whom I speak are somewhat selected, but I know a lot of them who are dreaming the big dreams about medicine; they're dreaming about making a change to the world – not just being changed by the world but making a change in the world, what stimulates them, and where they see themselves in the long-term – that's what I'm trying to encourage. It's not just about finding a big field of expertise, but about finding an area where you feel needed and where you can make a contribution. I never cared what my kids did, I care about people doing what they felt great about and really getting into it, really getting mastery of something.

Truffld: More than half of women are going into the medical profession now, but still not nearly as many in the surgical realm, and even less at executive levels. This could be multifactorial: perhaps men who run the organizations and maintain a glass ceiling for women, or women's confidence going into these roles, or a continuum of The Second Shift where women are still naturally taking on – even with supportive partners – most of the domestic responsibilities while working full-time jobs. Are these variables gating women the most, or something else you're seeing?

Dr. Ascher: When I was the Chair [of UCSF Department of Surgery from 1999-2016] 40% of the faculty were women and it wasn't because they were women, it was because I was selecting the best candidate. I think those numbers are changing a little bit, but what you say is absolutely correct: we've got men who are into the 'old boys' network, we've got women discriminating against women which is really disturbing; we shouldn't be surprised but it's there. And then I think what Covid-19 taught us was how really devastating these kinds of burdens are particularly on women. I don't mean to say men aren't burdened – many of them have lost their jobs, so many terrible things have happened to people – but I think that the pandemic has shown us that the burden of the family and the education has fallen on the mother, just as the teachers are burdened as well, and we have to do something about it.

Truffld: In various regions of the world and throughout demographics, the etiology of liver disease is going to vary. What are you seeing as the main cause of chronic liver disease in the US, and how can we work to maintain a more sustainably healthy liver throughout our lives?

Dr. Ascher: I'm glad you asked me that question [smiling]. In the US, fatty liver disease is important in terms of causing chronic disease and need for transplantation, a potential problem for us all: a pre-diabetic state, the use of fat, the use of sugar, our diet, the lack of physical activity. Hepatitis C isn't such a big deal anymore because we have effective, though expensive, treatment. Alcohol remains a giant problem in the US, so I'm not gonna preach to anybody but if you can exercise, watch your diet, not eat too much fat, sugar, or alcohol, you're probably going to live forever [laughing] – well, without liver disease, anyway, unless there's an underlying congenital reason for the disease, but those are much rarer than the self-inflicted causes.

Truffld: In the US there's a disproportionately low number of organ donors compared to those in need of transplant. Why is this the case, and how can we increase these numbers? Additionally, in one of your prior lectures, you cited a figure of 1.2% representing the number of organs annually trafficked by the US. Can you explain this further?

Dr. Ascher: For those who have signed their donor card, I think it's fantastic. I think that it would be even better if someone decided that he or she wanted to donate a kidney while they're still alive so that during their lifetime they can enjoy the gift that they've provided for someone else, which could save their life. I'm advocating for both deceased donation, but also live donation, too, as another option for people who might want to give a portion of their liver or one of their two kidneys.

The 1.2% figure you're referencing reflects the foreign nationals who come to the United States who get a kidney. Now, that 1.2% of the total transplants sounds like a teeny number, unless you're waiting for a kidney from the same place as that person coming who comes from Saudi Arabia, in which case you might feel that you're being discriminated against or passed over or cheated or you lose your place on the list if someone goes ahead of you.

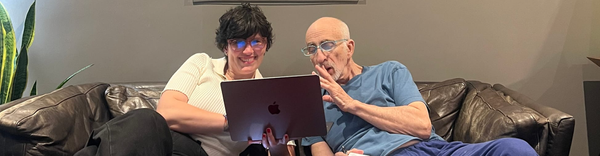

Truffld: During Netflix's, The Surgeon's Cut, your husband – who you work closely with [a transplant surgeon on the organ recipient side] – was asked about the things he's learned about working with you, and he said, humorously, that you were "impatient and strong-willed." How do you manage the separation of your work and home life, and how has working together so intimately, impacted your overall relationship?

Dr. Ascher: The people you work with – if you have a good working life – are people you really trust, and it's fantastic to be able to combine my work relationship with my personal relationship. But from a clinical standpoint, I really trust my husband's judgement, work ethic, and the work that he does. Can I give him more tips? Certainly [laughing], but I have incredible respect and admiration for him at work. We bring stuff home sometimes but we really try not to.

Truffld: The liver is highly regenerative, especially compared to other systems in the body. Advancements in medicine now center quite a bit on the use of stem cells, 3D-printed organs. What kinds of advancements are you excited about that are on the forefront at the moment?

Dr. Ascher: The liver is a bit more complicated than other organs. For example, the heart can be replaced with a machine or a printed heart, but it's much more difficult with a liver because of all of its functions. The use of stem cells though to help regenerate the liver could be within the five-year frame. There's also exciting things related to how the body adapts to the liver and how our patients can get by with less and less immunosuppression over time – so that's wonderful, and a natural experiment of the body and the liver.

The fact that we do the live donors is a major advance in the field of liver transplantation because it means that someone doesn't have to die for you to recover from your liver disease. There is risk to the donor, but the liver in the donor and the liver in the recipient both grow to normal size over time. Another exciting advance is that we can cut the liver into two for two different recipients, as well as the use of machines that allow us to keep the [deceased donation] liver out of the body for a period of time after donation to have it recover if it's somewhat diseased, until it can be transplanted – that will be a reality the coming months to a year. The direction we're headed is really exciting!