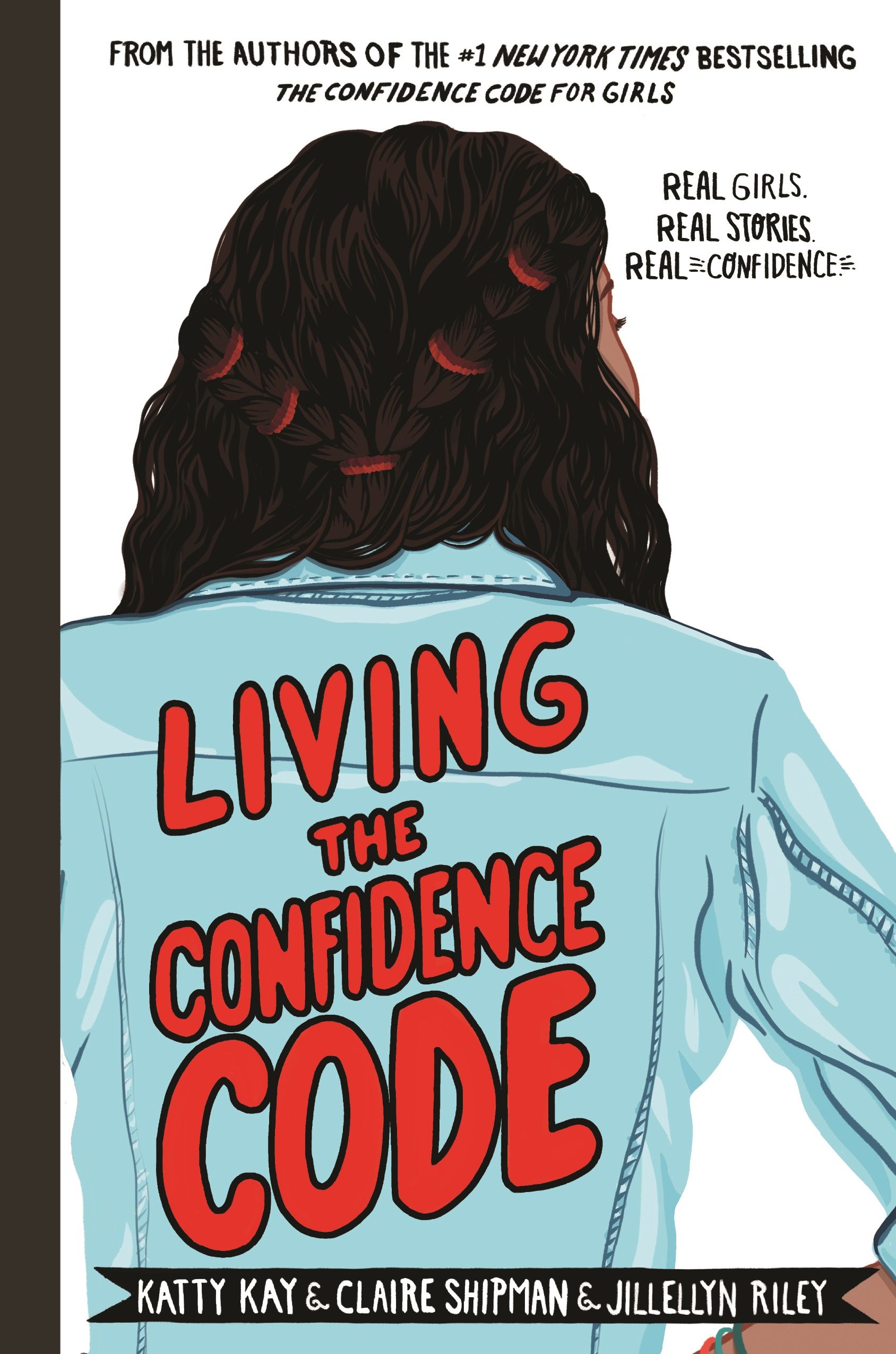

Decrypting Confidence with Katty Kay and Claire Shipman

Journalists Katty Kay and Claire Shipman chat with us about their research on girls' confidence, what we can do as parents, and the role of genes versus experience.

By Victoria Oldridge

Truffld: Living the Confidence Code is geared toward pre and post-adolescent girls, but I think it's really written for grown women – I found the raw stories of resilience, grit, and determination by these young girls to be as inspiring, if not more, than those of women with decades of experience under their belt.

Claire: I think you're right about the overlap. We learn from other people's stories, and in a lot of ways watching the girls go through things and making decisions, it's a crystallized version of some of the stuff we [as adults] have to deal with.

Katty: One of the things that our research has taught us, both for women and girls, is what psychologists refer to as 'volatile confidence' – the sort of confidence you get from social media, a compliment, or review on something; it can come and go. But what we've found is that stable, durable confidence comes from taking risks, doing hard things, and overcoming hurdles.

Some [girls] overcame bullying, while others formed organizations to clean up plastic in Indonesia, or bravely left a child marriage in Ethiopia, but the process in building their confidence was the same: taking risks, having courage, going through the struggle.

Truffld: How much of confidence can we attribute to nature versus nurture?

Claire: Some of it, about 20%-40% is inherited, but the bulk of it is created, and the interesting thing for parents to understand is – and it's been a struggle for me with my kids – is you don't create confidence by telling them they're great, patting them on the back, or solving problems for them.

What we've found that happens with girls, especially around puberty, is there's this people-pleasing perfectionism that sets in, and self-doubt; it seems for some parents that their girls have almost transformed overnight. As teachers and parents we feed into that because we love the 'good girl, make our lives easier' sort of qualities. Who doesn't love the girl who's always on time, gets good grades, etc.? But those qualities aren't necessarily what's going to build her confidence or help her survive in the real world. You need to be able to make mistakes and move on, which is a learning process for all of us.

Katty: Yes, there are genes that predispose us to either confidence or on the flip side, anxiety – that's broadly how psychologists and neuroscientists split it up. The 20%-40% figure [genetic predisposition] that Claire referred to is gender-neutral, but the difference is when the onset of estrogen happens for girls combined with a society that rewards girls for coloring inside the lines, being obedient, etc., and so you get that confluence for girls that doesn't happen for boys as much.

In Living the Confidence Code, we've wanted to show the girls who have also had failures and overcame them. Through research, we learned that girls have a tendency to do something psychologists call, 'catastrophizing.' Girls can go from 0-100 in 20 seconds: 100 being "I'm going to fail at everything, never have any friends, and end up living under a bridge." So that process of seeing the downside of risks looms so large that it sits oppressively on their shoulders, and that's something boys don't tend to do.

Claire: Exactly. For example, I recently took my daughter to practice driving and she automatically assumed people were honking at her and that she did something wrong. I said, "Please try to channel your brother who sits in a car and feels like 'I'm so cool, I'm in a car.'" She automatically took it to heart when the honking had nothing to do with her.

Truffld: When we detect that our child might not try something new due to lack of confidence, as a parent, it's a fine line when figuring out when or if to push them harder outside of their comfort zone. How can we enable them to unfold when we notice that confidence could gate that growth?

Claire: I've done it really badly, so I can speak to that [laughing]. While working on the first book [Confidence Code for Girls], I thought 'Yes, clearly my daughter just needs to get out there,' and I forced her in middle school to sign up for the debate team which was entirely not her thing, and when I say she was traumatized by that experienced, she was frozen – I figured she'd get over it. So I think it's important to help our kids to identify a reasonable risk where there's a bit of a net underneath that they can absorb, but also even at the dinner table, don't just talk about what you've done well, discuss what you've failed at that day. Let's say, "Great job trying, that must have been so hard." If you can knit together something that happened 3-4 months before, and pull it together for them in a story and say, "Do you remember how horrible you felt that day? And look at where you are now. Look at what you've done." They really remember their own stories.

Katty: Be careful of what you're doing, too, because we know that girls are prone to perfectionism. If you go home and try to be a perfectionist, what is your child or daughter going to see? That's their role model, so talk about when you've messed up. Let's normalize that process, because we all do [mess up], and the more you can learn, respond, and bounce back, the happier and more confident you'll be.

Follow on IG: @Confidence Code Girls @theshelfstuff @harperkids

Facebook: @theconfidencecode @theshelfstuff @harperkidsbooks

Twitter: @harperchildrens

Hashtags#confidencecode

#livingtheconfidencecode