Dr. Robert Stickgold on: 'We Are What We Sleep,' and Rethinking Going to Bed Angry

Dr. Robert Stickgold, featured in Netflix's The Mind Explained, chats with us about the profound impact of sleep -- from vaccine efficacy, to strengthening relationships.

by Victoria Oldridge

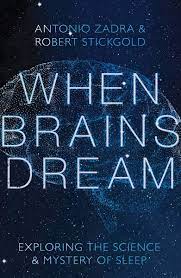

Robert Stickgold is a professor of psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, and has published over 100 scientific papers, including in Science and Nature, and his work has been written up in Time, Newsweek, and The New York Times. He studies the nature and function of sleep and dreams from a cognitive neuroscience perspective, with an emphasis on memory processing. He also investigates alterations in sleep-dependent memory processing in patients with schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder, and PTSD. His work is funded by NIMH. He is coauthor, with Antonio Zadra, of the new book, When Brains Dream.

Truffld: In When Brains Dream you explain that sleep helps us to form memories which inform our sense of self, and that our dreams' purpose is to identify, explore, and evaluate the significance of daily events, and to sift through neural networks. If the quality of our sleep is interwoven with the elements and moments from the day that our brain decides to 'tag,' and that dictates the memories that are created, then this supports the quote in your book, “We are what we sleep.” Ultimately, our sleep then determines our sense of self.

Dr. Stickgold: The brain will take information, integrate it with some old memory you have that you never would have though of combining it with during your waking time. People say to me, 'My memory’s fine. I don’t have any issues with it.' And I hate to say it, but I tell them it’s shallow memory, because the difference between being smart and being wise is in the quality of their sleep.

You can have poor sleep and still have great rote memory – someone will take a test and still have all of the key facts memorized. But they may have struggled on a comparative essay portion, for example, because they're not going through all of the necessary sleep stages throughout the night that facilitates synthesis of information. Now, we don't know exactly how the brain decides to 'tag' certain moments or events, but it does. There are 15 billion neurons and 124 trillion connections between them; that's 1000 times more connections than stars in the milky way.

If I were to ask you to tell me about yourself, at the first level you’ll tell me some basic information. And then, if you’re foolish – or if I’m trustworthy – you start to tell me about who you really are. During my sophomore year of high school, I can remember so clearly being in a chorus performance rehearsal and some other student was playing a song on the piano, and I turned to the person next to me and asked if he was playing a certain song – trying to appear knowledgeable – and he looked at me like I was an idiot and he said, 'No, it’s Rhapsody in Blue.' And I decided right then that I had to learn classical music. I mean, what a bizarre moment and cause for it. But I made that decision.

When I went off to college three years later, I bought Boston Symphony season tickets, listened to a Chicago classical music station all day long even to today. Is it really all because of that sophomore year conversation? I don’t even remember what I sang in that chorus because for some reason, my brain decided it didn’t care about that; it didn't tag it as significant. So, if we talk for many days and evenings, you start to tell me about the events of your life like this one I shared, and then we really start to learn about who each other is.

Truffld: I also read that sleep can have a pronounced impact on the efficacy of vaccines. As we continue to navigate Covid-19, I wonder about the variability of immune response that people are experiencing, especially due to our country's poor sleep regimen.

Dr. Stickgold: You give someone a hepatitis or flu vaccine and it’s not that they don’t produce any antibodies, it’s that they produce a third less if they don’t sleep well before and after the vaccine [*see study references below]. I actually wrote – after I read your pre-questions about the impact of sleep on antibody production related to the Covid vaccine – to the Director of the CDC, Rochelle Walensky, and I wrote: a) you have to tell people that if they don’t get sleep the night after they get their Covid vaccine, they’re not going to be protected from it, and b) then you have to collect the data. You have to say, 'When you go to get your Covid vaccine, you need to fill out this questionnaire that asks how much sleep you’ve had over the past five nights, and we have to warn you to get a full night’s sleep tonight,' and then see what the data looks like.

Truffld: Studies show that decrease in sleep duration and quality result in a slew of chronic illnesses, from Alzheimer’s, due to B-Amyloid build-up; diabetes, due to increased insulin resistance; compromised immune response, and a host of other conditions.

Dr. Stickgold: Yes, that's right. And in adolescence, 90% of the growth hormone is released during slow-wave sleep. So not only do you need sleep, but you need quality, deep sleep. The good news is that you get all of your slow-wave sleep in the first half of the night, so if kids are getting a solid four to five hours of sleep, they’re getting their growth hormone – they won’t though, get into REM sleep so they won’t be synthesizing what they’ve learned during the day.

We don’t know which sleep stages are associated with lowered immunity, but we do know that less sleep could cause stress [and vice versa], so perhaps managing stress levels while you sleep is what needs to happen. For example, we also know that flight attendants who do transcontinental shifts frequently, having to switch time zones and sleep cycles, have higher breast cancer rates compared to those who fly coast-to-coast and go home to sleep at night in their usual time zone.

Truffld: Our society in particular suffers quite a bit with insomnia, anxiety, and generalized sleeping disorders, in part, as you’ve stated, because we’re too 'plugged-in' throughout the day, so our brains aren’t able to process in real-time. Instead, we're bombarded with a myriad of thoughts and concerns when our head hits the pillow at bedtime. How can we mitigate this universal, nightly ritual so that we then don’t suffer the downstream health effects of inadequate sleep?

Dr. Stickgold: People like Oprah always say, 'don’t go to bed angry,' and I think that’s kind of what you’re saying: process these things to a point during the day where your brain can deal with it at night without it being so ramped-up. I don’t know that we have to do something explicitly intentional to mitigate this issue. It’s more about what we shouldn’t do. When you walk down the street you don’t see people who aren’t plugged-in. It’s really strange. When you go to a party, for example, they set the music to a level where you can’t think, because the belief and the culture is that you go to a party to just relax and not think. But we carry that noise into our whole day.

Going back to not going to bed angry: There’s this thing about relationships – if you’re not spending a certain amount of time actively working on it, then all that’s really left is the crap. So when you finally do have half an hour with your partner or with a friend, you don’t have time to talk about the good stuff because the bad stuff has to be dealt with. As we decrease the amount of time we spend alone with ourselves, to mind wander, to daydream, to muse, what happens is when we do have those alone minutes we have all of the hard, unpleasant stuff to deal with – that has to on some level be dealt with first, and then being with yourself unfortunately becomes aversive.

Truffld: Is there an ideal equation for sleep in terms of overall health optimization, or do we gauge it based on how we feel each day?

Dr. Stickgold: Sleep as much as you truly want to [easier said than done]. If you spontaneously wake up after five hours of sleep and jump up awake and alert, then go for it. If you can sleep every night as though you were on vacation, that’s the right amount of sleep. You know when you come back from that perfect vacation and walk into the office on your first day back, and you can’t even remember what you’re supposed to be doing? That’s how you give your brain what it needs to do while you sleep. For every two hours of information input, you need an hour of sleep to process it.

Truffld: In When Brains Dream you referenced the stress of having to do the heart dissection of a dog during graduate school and the nightmares that ensued in association with your infant daughter at the time, and that years later you had a son who was born with a congenital heart defect that required heart surgery at four months. You went on to explain that as much as we’d like to think that our dreams might be some sort of foretelling or 'magical' thinking of sorts, that the science tells us that’s not the case. I think that there’s an entrenched human desire to want to believe that dreams are some other dimension of something or other that’s trying to convey something to us outside of everyday life. But you also said, encouragingly, that despite the advancements in science, 'our dreams’ magic, mystery, and wonder will remain.'

Dr. Stickgold: My wife and I are both Jewish – she more than I – and she describes me as her 'beshert,' who’s the person that from the time we were born, we were meant to be with; a prescribed soulmate. There’s something wonderful to think that through all of the classes, parties, conventions, and crowds, that we were meant to come together. I don’t believe in that, but I think it’s equally awesome that we found each other anyhow. And I do think that our dreams tell us a lot. The answer is, our brains are creating wondrous discoveries as we dream. It’s putting things together in ways that tell us something that we would never know otherwise. I tell people, 'Never marry anyone because of a dream and never divorce anyone because of a dream,' but listen to what it has to say and wonder why.

I think it’s pointless to say that our only purpose in life is to survive and reproduce. We’re so much more than that. We create meaning, and meaning is an amazing thing – from a piece of music, to a poem, to something you blurt out to a friend that stops them in their tracks because they had an epiphany. You can find wonder in what’s there already. The questions that science answers are not questions of the heart, they’re questions at some level, of the mind. That won't change.

Truffld: On that note, thank you for the breadth of research you’ve contributed throughout the decades. I hope to be firing on all cylinders the way you are during this chapter of your life when I reach it, and thank you for taking the time to speak with me.

Dr. Stickgold: Thank you, and please, just don’t talk to my wife about my memory.

*Study on sleep deprivation following hepatitis B vaccine

*Study: Sleep enhances the human antibody response to the hepatitis A vaccination.

To learn more about Dr. Stickgold, watch Netflix's series, The Mind Explained (Dreams episode), and purchase this year's release of his book, When Brains Dream.