Interview with Entrepreneur and Author, Luke Burgis: Getting to the Root of Our Desires, Choosing Wisely, and Being Intentional About Our Influences

Ever wonder why you chose a certain career path, place to live, car, hobby? What drives your relationships? To understand, perhaps we should choose our 'models' first.

by Victoria Oldridge

Luke Burgis has co-created and led four companies in wellness, consumer products, and technology. He’s currently Entrepreneur-in-Residence and Director of Programs at the Ciocca Center for Principled Entrepreneurship where he also teaches business at The Catholic University of America. Luke has helped form and serves on the board of several new K-12 education initiatives and writes and speaks regularly about the education of desire. He’s Managing Partner of Fourth Wall Ventures, an incubator that he started to build, train, and invest in people and companies that contribute to a healthy human ecology.

Truffld: You explained in WANTING that you went through an involved business – which morphed into a friendship – courtship with Zappos founder, Tony Hsieh leading to an anticipated acquisition of your company which fell through in the 11th hour. Though you rebounded and went on to experience more fruitful outcomes as a founder, what struck me was the "emptiness" you discovered when you arrived at those successes. Looking back, was it your expectation of that endpoint that disappointed you, or a lack of meaning throughout the endeavor to begin with?

Luke: I think it stemmed from forgetting who I was in the process of very passionately pursuing models that I had adopted from a very specific world in Silicon Valley. Certain goals were given to me that were never entirely my own; they were just adopted without my having giving them a lot of thought. So when I achieved them, their emptiness was revealed to me, and there was nothing there that satisfied a real sense of fulfillment for me. Later in the book when I talk about the difference between 'thin desires' and 'thick desires,' that's what I'm getting at: these were thin, highly mimetic desires that I adopted and pursed and achieved [in most cases] and they were just like water, very ephemeral and fleeting – they didn't leave me with any sense of enduring satisfaction.

The other part of it is that I didn't know myself very well at that part of my life; I hadn't done a lot of introspection and self-discovery, so when one doesn't know themselves very well, they construct themselves through the most powerful models around them – it's almost more of an occupational hazard for a highly ambitious person like me, who, when I set my mind to something I really pour myself into it. All of the narratives that I had told myself meant that I started to identify with a certain kind of person. Sometimes I look back and wonder, if the Zappos deal hadn't fallen apart if I would have continued telling myself that story for the rest of my life. So in a way, it was this tremendous blessing for me to have the clothes torn off and to see myself standing naked in a sense, and to see all of these things that I thought I cared about, I actually didn't, and that's why I felt this enormous sense of relief when the deal fell through; I felt like I was getting a second chance to actually take some time away to think about what it was I truly wanted to do in the next ten years.

Truffld: Did you feel then, after that revelation, that you were more cautious about filtering the models around you, to be more discerning about carefully choosing those that were more purpose-driven and that you could identify with?

Luke: I had a lot more intentionality about the influences I allowed in my life. One of the things I noticed as a young entrepreneur, at the time that deal fell apart, was that a lot of the people and models that I admired the most came from outside the startup world. So that was a hint for me: The things I desired the most – more balance, family life, my faith was starting to become more important to me – I was not able to find some of those things inside of the startup arena. It let me know that maybe I needed to expand my models of desire outside of the very small world that I was in. What I deemed as fulfillment couldn't be found entirely there, even though some aspects of myself were, like my intense drive for creativity, to be around smart people. But yes, I needed to be more intentional and to cultivate sort of a composite by expanding my universe a bit.

Truffld: When we talk about mimetic 'triggers' of sorts, I think of present-day entities that come to mind that throw people into a concentrated state of wanting to imitate others or desire what others have, and social media stands out likely as the top influence. But what about more remote, perhaps even tribal regions of the world where technology is less of a focal point, and the communal 'we' versus 'I' sort of mentality is priority; wouldn't there be less mimetic desire in that scenario?

Luke Burgis: I'm not sure about that because it could actually be the opposite. I think technology is accelerating the movement into small, close-knit clusters of people, partly through mimesis and then these groups are bound together through some sort of shared identity because it's easier to find those people than ever before because of technology, which is one of its great virtues. But in a sense it's driving everybody into these micro-clusters.

I think one of the things the pandemic did in my view, for example, is make the world a little bit more mimetic as many of us spent more time online, more time on social media, which makes us more susceptible to comparison and adopting people on social media as models. The people that run the platforms, I don't know if they know explicitly, but I think they might know tacitly that mimetic desire is their friend in the sense that the more mimetic desire these platforms generate, the better that they do.

Another example: What we saw happen in the stock market for the first time – I don't think I've ever seen anything happen quite like that – René Girard would say that the stock market is the most mimetic institution; I would say that social media is right up there with it. So, the wild volatility, the meme stock phenomenon, it's no coincidence, I think, that this emerged during the pandemic while these groups on sub-reddit forums, for example, were driven through mimesis to cluster around certain things, I saw mimetic desire in many ways. And the 'we' part of that – it's a double-edged sword.

Emile Durkheim talked about this phenomenon of collective effervescence – everyone at a party is dancing and singing, but that can be good or it can be bad though, because that same collective effervescence has a dark side that can turn into mob-like behavior and violence. I think that those healthy communities can form, but I worry that the mimesis that we're seeing now is actually forming some unhealthy tribalism.

Truffld: René Girard says that we're incapable of spontaneously cultivating our own desires and that they're all based off of other models, so how can we at a minimum, take actionable steps to do the work to get closer to developing desires based on a healthy, beneficial premise, and to circumvent the less advantageous drivers of desire?

Luke: We're social creatures so the nature of desire is social, therefore there's a certain amount of acceptance in that. We need to understand that we see ourselves in the other and in a sense that's a beautiful thing; it's what makes love and relationships possible. The goal isn't necessarily to become less mimetic – it's to develop more intentionality and be able to see the way that desires are taking shape in yourself and perhaps in the culture.

There's this tremendous explanatory power in understanding mimetic desire in rivalry – to sort of make sense of the seemingly irrational behavior that we see around us. Mimesis exists on a spectrum. It's not that some people are totally mimetic and some aren't. The key is understanding where we fall on that in certain relationships in our lives; in relation to certain groups or people or things. It's helpful to ask: What is it about this particular person or group that has led me into some kind of obsessive desire to have what they have? Or why don't I necessarily care about other aspects of success? What does it say about me? What does it say about the kind of relationship that I'm in with this person or group, and do I need to change it? Do I need to model a different way of being in relationship? My goal is really awareness, not necessarily escape.

Learn more at Luke Burgis

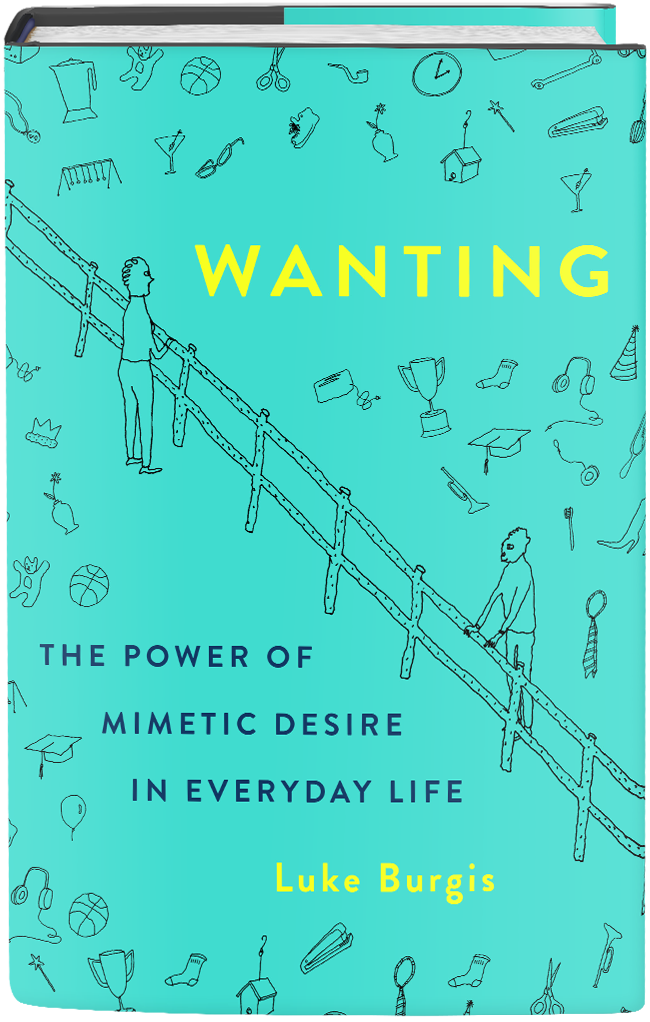

Book: WANTING

Twitter: @lukeburgis

IG: @lukeburgis

Facebook: @lukeburgis